March 2, 2020

If you want to lose fat, improve metabolism, and experience other health benefits all without extreme or restrictive dieting, intermittent fasting might be for you!

Intermittent fasting (IF) is an emerging area of research and the results are very promising. Similar to calorie-reduced diets, IF has benefits for weight loss and metabolic improvements. It might even boost brain and mental health—improvements that would undoubtedly benefit an athlete.

In terms of weight loss or maintaining body weight for sport and working out, intermittent fasting (IF) has a few advantages over regular calorie-reduced diets. Not only is it easier for many people to stick with, rather than restricting calories every day, it also seems to have a metabolic advantage.

So let’s dive into it.

What is Intermittent Fasting?

Intermittent fasting (IF) is just that—fasting, or going without eating—intermittently (periodically). Before you panic at the thought of going days without eating, IF typically refers to short time periods. As opposed to fasting for days, we’re talking hours—Oh, thank goodness! More good news, IF doesn’t necessarily mean reductions in total daily calories either. This is extra beneficial for the athlete who needs to hit his/her daily caloric needs for performance and recovery, but still looks to lean out a little.

Intermittent fasting is an “eating pattern” rather than a “diet.” It’s controlling when you eat and drink, as opposed to how much or what you eat and drink. More good news for those who dread the idea of measuring or tracking every last bite.

But before you get too excited, this doesn’t mean that it’s a free-for-all during your eating times! Good quality whole food is still recommended in the appropriate serving sizes for your goals (we can help figure out what that is for you). However, eating within a designated time period—or an intermittent eating window—might be as beneficial as focusing on what or how much you eat.

There are lots of ways to intermittently fast. It can be done daily, weekly, or monthly. After we go over the health benefits, we’ll look at some of the most popular methods on how to—and who shouldn’t—IF.

Get ready to have amazing energy, optimal performance, and finally shed those last 10 pounds (or the first 20 or 30)!

We use intermittent eating in our Food Camp Fundaments nutrition program. Learn how to implement IF knowing you’re meeting all your nutritional needs. Plus, it includes everything else you need to build your best body from the inside out.

Check out Food Camp Fundamentals here

Background: History and Animal Studies

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. studies looked at effects that reducing smoking had on heart disease risk. Interestingly, the risks seemed to reduce more in members of the Churches of Latter Day Saints and Mormons than in other people. Researchers wanted to know why, and that’s when they found a possible connection with fasting.

Beyond smoking, researchers started looking specifically at people who fasted. In the early 2000s, they found that people who reported routine fasting (for religious reasons or not) had a lower risk of heart disease, blood sugar levels, body-mass indices (BMIs), and risks of diabetes.

It’s easy to restrict when an animal eats, so there are a lot of studies on the health effects of IF in animals. They show health benefits, including longer lives and reduced risk of atherosclerosis (narrowing of the blood vessels due to buildup of plaque), metabolic issues (includes type 2 diabetes), and effects on cognition (ability to learn, remember, solve problems). They also have lower levels of inflammation and generally live longer.

Both animal studies and human observation have shown great promise.

So, let’s dive into the health benefits of IF.

Intermittent Fasting for Weight and Fat Loss

For people who have excess weight, losing weight and fat reduces the risk of diabetes, improves healthy lifespan, and increases function of both the body and mind. This would surely contribute to improved performance not only for competitive and recreational athletes, but all who work out regularly.

Studies show that after losing about 5-6 percent of a person’s body weight, even more health benefits are seen:

- lower blood lipids (LDL cholesterol and triglycerides)

- better blood sugar management (lower glucose and insulin)

- lower blood pressure

- lower levels of inflammation (C-reactive protein)

This is all good news for the athlete who’s prone to increased inflammation as a result of high-level training! The increased need for simple sugars to fulfil energy demands often predisposes athletes to blood sugar imbalances as well. Thus, improved blood sugar management correlated with IF makes good sense.

When it comes to weight and fat loss, a typical calorie-reduced diet works by moderately reducing how much is consumed. This is called “continuous” calorie reduction because one is continuously reducing: at every meal and snack, every day on an ongoing basis.

Intermittent fasting isn’t a continuous reduction in calories, but rather an “intermittent” one. It allows you to eat more of the healthy foods you want, but only during certain times. It’s an alternative to overly restricted calorie diets. Intermittent fasting is a way to “diet” without “dieting” all the time, so to speak.

Studies show that both continuous calorie reduction and IF have similar weight loss results.

But . . .

Intermittent Fasting Has a Few Key Benefits!

Many studies prove what we know already: It’s really difficult to sustain a (continuous) calorie-reduced diet for a long time. This is the reason why many people prefer intermittent fasting. It accomplishes similar weight and fat loss results, plus it’s easier for many people to stick with.

Also, some studies show that IF makes our metabolism more flexible so it can preferentially burn fat while preserving muscles. This is another great benefit for the athlete working to lean out without losing hard-earned muscle mass.

Intermittent Fasting for Metabolic and Heart health

Over and above the weight and fat loss benefits, IF has metabolic benefits. IF may help not just with overweight and obesity, but with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease as well.

People who IF sometimes have improved insulin sensitivity and blood sugar levels. They also show improved blood lipids and even reduced inflammatory markers. All of these relate to improved metabolism and reduced risks for many chronic diseases.

One study found that people who IF’ed for 6-24 weeks and lost weight also benefited from reduced blood pressure.

One unique way IF works is by making our metabolism more flexible, which we’ll talk about below. This is really important for blood sugar control and diabetes risk because according to Harvie (2017):

“Metabolic inflexibility is thought to be the root cause of insulin resistance.”

Another researcher, Anton (2015), says:

“When taken together with animal studies, the medical experience with fasting, glucose regulation and diabetes strongly suggests IF can be effective in preventing type 2 diabetes.”

Most researchers find these results promising. They still recommend more high-quality longer-term trials, including ones on intermittent fasting and working out.

Intermittent Fasting for Brain and Mental Health

Many animal studies show that intermittent fasting can help improve their cognition (ability to think). When mice fasted on alternate days for 6-8 months, they performed better in several learning and memory tests, compared to mice that were fed daily. This improvement even happened in mice who started IF later in life.

Studies also show that alternate day fasting protects brain neurons in animal models of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke. It also reduces oxidative stress in the brain.

Researchers are still learning about the brain and mental health benefits of IF in people. Short-term studies show some people report improvement in tension, anger, and confusion from IF; while others report bad temper and lack of concentration as side effects from it.

More longer-term human studies are needed to shed more light on the effects on cognitive performance and mental health.

How Intermittent Fasting Helps Our Bodies and Brains

How do we explain the health benefits that IF has on our bodies and brains? One way is the “metabolic switch” that is flipped during fasting.

While continuous calorie reduction and IF have many of the same health benefits, IF might have a different biological mechanism at play. Some research suggests that IF might “flip” a metabolic switch.

Here’s how it works.

After we eat, our bodies use carbohydrates (e.g., glucose) from our food for fuel. If there is extra left over, then it’s stored as fat for future use.

With fasting, just as during extended exercise, our bodies flip from using glucose (and storing fat), to using that stored fat and ketones (made from fats) for fuel. Sometimes called the “G-to-K switch,” (glucose-to-ketone) the ability to flip what our bodies use as fuel (between glucose and ketones) is called “metabolic flexibility.”

It’s thought that we, and many animals, evolved to have this ability to survive short periods of fasting from when we were hunter-gatherers. There were times when people didn’t have a lot to eat, but they still needed to survive and think clearly enough to successfully hunt and gather food. This can explain why our bodies and brains don’t necessarily become sluggish when we’re fasting. It makes a lot of sense, although it has yet to be tested in current-day hunter-gatherers.

This metabolic switch can explain some of the health benefits of fasting. When our bodies prefer using fats for fuel, the body starts burning our stored fat. This is how IF helps with overweight, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. When the body uses fat for energy, this decreases the amount of fat in the body. Reduced fat reduces weight, and health benefits from weight loss (like lower blood pressure and insulin resistance) are felt.

This “flipping” of the metabolic “switch” happens after the available glucose and the stored glucose are depleted. This is anywhere from 12-36 hours from the last meal, depending on the person. At this point, the fats in our cells start getting released into the blood and are metabolized into ketones. These ketones then go to fuel cells with high metabolic activity: muscle cells and neurons.

Because the body is burning fat and using ketones to fuel the muscles, IF can preserve muscle mass. Some studies of IF show that it preserves more muscle mass than regular “continuous” calorie-reduced diets do. This is great news for athletes and others who work out.

The other high metabolic activity cells fueled by ketones are neurons (in the brain and nervous system). Intermittent fasting helps our brains because when our neurons start using ketones for fuel, it preserves brain function and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is very important for learning, memory, and mood. It also helps enhance synaptic plasticity (changes in our brain that help with learning and memory) and allows our neurons to better resist stress. These are all improvements in brain function, and some animal studies also show improvements in the structure of the brain too. For example, new neurons are produced in the hippocampus (the part of the brain important for short- and long-term memory) in animals who IF.

According to Anton, 2018:

“In these ways, events triggered by the metabolic switch may play major roles in the optimization of performance of the brain and body by intermittent fasting.”

Who Shouldn’t Try Intermittent Fasting?

PRO TIP: Before you try any major changes to your diet, check with your healthcare provider.

Intermittent fasting can provide a lot of health benefits and, according to Patterson & Sears (2017):

“Overall, evidence suggests that intermittent fasting regimens are not harmful physically or mentally (i.e., in terms of mood) in healthy, normal weight, overweight, or obese adults.”

There are a few things to keep in mind before considering intermittent fasting, however.

A number of adverse effects have been reported, including bad temper (yup, we’re talking hangry!), low mood, lack of concentration, feeling cold, nausea, vomiting, constipation, swelling, hair loss, muscle weakness, uric acid in the blood and reduced kidney function, menstrual irregularities, abnormal liver function tests, headaches, fainting, weakness, dehydration, mild metabolic acidosis, preoccupation with food, erratic eating patterns, binging, and hunger pangs. Many of the negative symptoms experienced when fasting for prolonged hours can be the result of low blood sugars. Be sure to check with your physician or qualified nutritionist if low blood sugar might be an issue for you.

If done too often or for too many days IF can have more serious effects.

Fasting for several days or weeks becomes starvation even in healthy adults. At this point, your body starts consuming muscles and vital organs. Excessive fasting can lead to malnutrition (including vitamin B1 deficiency), decreased bone density, eating disorders, susceptibility to infectious diseases, or moderate damage to organs—none of which will support any type of sport, period.

Limit fasting to avoid these effects.

How to Intermittently Fast

There are lots of ways that people intermittently fast. We don’t yet know how these different methods have different health effects for different people with different health goals, including athletes.

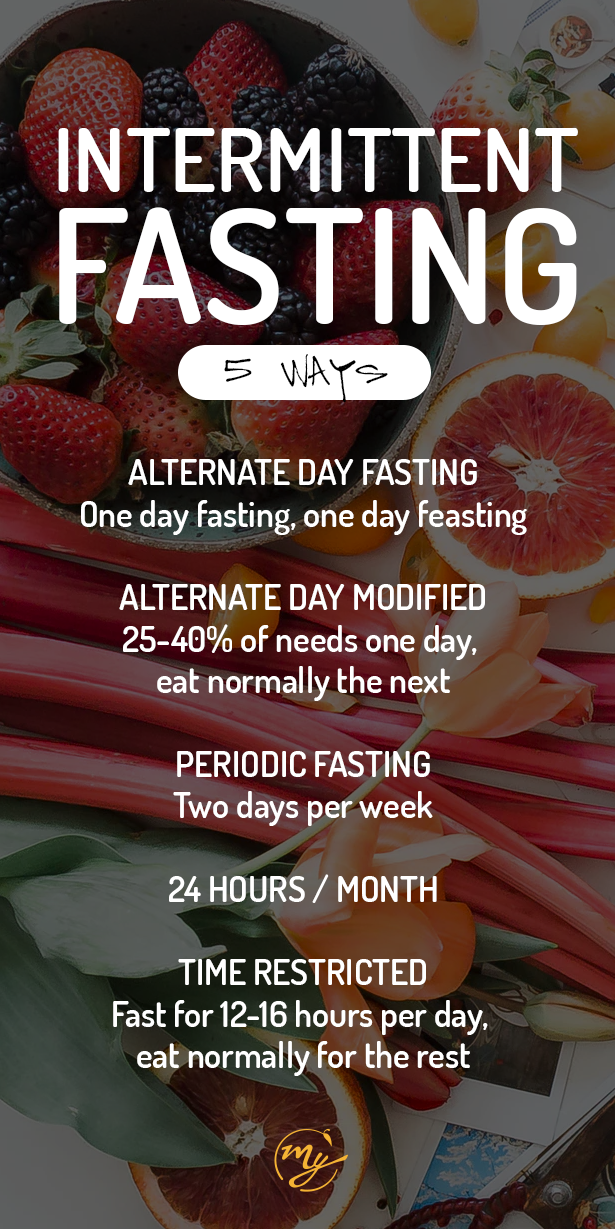

Here are some different ways people IF:

-

Alternate-day fasting (ADF) – One day of fasting, one day of “feasting.” Continue fasting on alternate days. We don’t recommend this for active individuals who are working out.

-

Alternate-day modified fasting (ADMF) – Eat 25-40 percent of your daily needs one day, then eat normally the next. Continue alternating days.

-

Periodic fasting (PF) or “Two day” fasting – Each week has one or two days to eat very few calories per day (e.g. 0-880 cal/day). The other five days you eat normally. Example: 5:2 diet, where you eat no more than 500 calories/day for two non-consecutive days each week. This could fit an athlete’s training schedule by fasting or eat lightly on your days off, while training days have normal calorie intake.

-

One 24-hour period of fasting each month.

-

Time-restricted fasting (TRF) – Fast for 12-16 hours every day and eat normally during the other 8-12 hours. This one is our favourite for athletes and those who work out!

As an athlete, I have found both for myself and my clients that the time-restricting eating (yup, I like to focus on the “eating” rather than the “fasting” ☺ ) works quite well. However, instead of 16-8, we recommend closer to 14-10 or even 12-12 to start. This way ensures you have the fuel you need for working out, regardless of what time of day you do it. Alternatively, one day of fasting monthly (on a day off from training) is also effective.

When experimenting with time-restricted eating, we recommend you gradually reduce the window of time in a day that you eat. For example, if you typically eat breakfast at about 7 am and have your last snack of the day at about 9 pm, that means your total eating window is 14 hours. Begin by reducing that by a couple of hours. Perhaps you’ll have your last evening snack no later than 7 pm, making your new eating window 12 hours. This would be a 12:12 cycle and would result in the benefits noted above.

Intermittent Fasting and Working Out

Don’t lose that muscle!

When it comes to preserving muscle mass, the jury is out on IF, but here are a few tips:

-

Continue eating enough protein (1.2+ g protein/kg weight depending on your individual needs and your sport)

-

Include resistance training to build or maintain muscle mass

-

Ensure adequate total daily calories and carbohydrate intake for your needs

Get in touch with us to chat about determining what your macronutrient needs are for your goals.

Will you eat more?

You may be wondering if intermittent fasting increases what you eat during those times when you do eat. And that’s a great question. The interesting thing is, it seems not to!

Studies show that alternate-day fasting reduces overall calorie intake. Plus, on the non-restricted days, some people naturally reduce their energy (aka calorie) intake by up to 20-30 percent. This may be because we slowly adapt to not have our bellies full all the time!

BONUS: Another side benefit of IF is that it can help reduce food costs, too!

PRO TIP: Keep in mind that reducing your total food intake also reduces your nutrient intake. It’s important to ensure you get enough essential nutrients for both your energy and athletic needs and for long-term health. That’s why food quality is still important! Nutrient-dense whole foods are typically much lower in calories overall. Eating high quality, nutrient-dense food often results in less hunger and cravings, as your body is getting the nutrition it needs—even if that’s in less total calories.

Get ready to have amazing energy, optimal performance, and finally shed those last 10 pounds (or the first 20 or 30)!

We use intermittent eating in our Food Camp Fundaments nutrition program. Learn how to implement IF knowing you’re meeting all your nutritional needs. Plus, it includes everything else you need to build your best body from the inside out.

Check out Food Camp Fundamentals here

Take Away For Today

Intermittent fasting eating is a way to get the benefits of a regular calorie-reduced diet without excessively restricting what you eat. It simply restricts when you eat. Eating within a timed window reduces both weight and fat, and can improve blood sugar and blood lipids. It has been shown to reduce blood pressure and some markers of inflammation and may improve brain health too.

While these benefits of IF are similar to those with calorie-reduced diets, IF has some key advantages. These include being easier for some people to stick with and it might help people eat more intentionally. There is also evidence that IF preferentially reduces fat while preserving muscle and may help our bodies become more “metabolically flexible.” These are particularly important for athletes and those who work out.

More research is needed to really understand the long-term benefits of IF on the body and brain, as well as which IF approach is optimal for different people and different health goals. Like all intentional diet measures, it may offer benefits for some and should be discussed and monitored.

Need more info or support, get in touch—we love hearing from you!

Wanna chat more about meeting your nutritional needs?

Get in touch today!

We love hearing from you 😁

References

Anton, S. D., Moehl, K., Donahoo, W. T., Marosi, K., Lee, S., Mainous, A. G., … Mattson, M. P. (2018). Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 26(2), 254–268. http://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22065

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5783752/

Antoni, R., Johnston, K. L., Collins, A. L. & Robertson, M. D. (2016). Investigation into the acute effects of total and partial energy restriction on postprandial metabolism among overweight/obese participants. Br J Nutr, 115(6), 951-9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515005346.

LINK: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/53531AD2D87F6EAF46882955EC832A80/S0007114515005346a.pdf/div-class-title-investigation-into-the-acute-effects-of-total-and-partial-energy-restriction-on-postprandial-metabolism-among-overweight-obese-participants-div.pdf

Brandhorst, S., Choi, I. Y., Wei, M., Cheng, C. W., Sedrakyan, S., Navarrete, G., … Longo, V. D. (2015). A periodic diet that mimics fasting promotes multi-system regeneration, enhanced cognitive performance and healthspan. Cell Metabolism, 22(1), 86–99. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.012

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4509734/

Carter, S., Clifton, P. M. & Keogh, J. B. (2016). The effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; a pragmatic pilot trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 122, 106-112. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.010.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27833048

Clifton, P. (2017). Assessing the evidence for weight loss strategies in people with and without type 2 diabetes. World Journal of Diabetes, 8(10), 440–454. http://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i10.440

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5648990/

Fontana, L., & Partridge, L. (2015). Promoting Health and Longevity through Diet: from Model Organisms to Humans. Cell, 161(1), 106–118. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.020

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4547605/

Harvie, M., & Howell, A. (2017). Potential Benefits and Harms of Intermittent Energy Restriction and Intermittent Fasting Amongst Obese, Overweight and Normal Weight Subjects—A Narrative Review of Human and Animal Evidence. Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 4. http://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010004

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5371748/

Headland, M., Clifton, P. M., Carter, S., & Keogh, J. B. (2016). Weight-Loss Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intermittent Energy Restriction Trials Lasting a Minimum of 6 Months. Nutrients, 8(6), 354. http://doi.org/10.3390/nu8060354

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4924195/

Horne, B. D., Muhlestein, J. B., Lappé, D. L., May, H. T., Carlquist, J. F., Galenko, O., Brunisholz, K. D., & Anderson, J. L. (2013). Randomized cross-over trial of short-term water-only fasting: metabolic and cardiovascular consequences. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 23, 1050–7.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23220077

Horne, B. D., Muhlestein, J. B., & Anderson, J. L. (2015). Health effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr, 102(2), 464-70. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.109553.

LINK: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/102/2/464/4564588

Hussin, N. M., Shahar, S., Teng, N. I. M. F., Ngah, W. Z. W., & Das, S. K. Efficacy of fasting and calorie restriction (FCR) on mood and depression among ageing men. J Nutr Health Aging, 17, 674–80.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24097021

Keogh, J. B., Pedersen, E., Petersen, K. S. & Clifton, P. M. (2014). Effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on short-term weight loss and long-term weight loss maintenance. Clin Obes, 4(3), 150-6. doi: 10.1111/cob.12052.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25826770

Li, L., Wang, Z., & Zuo, Z. (2013). Chronic Intermittent Fasting Improves Cognitive Functions and Brain Structures in Mice. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e66069. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066069

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670843/

Mattson, M. P., Moehl, K., Ghena, N., Schmaedick, M., & Cheng, A. (2018). Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 19(2), 63–80. http://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.156

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5913738/

Michalsen, A. & Li, C. (2013). Fasting therapy for treating and preventing disease – current state of evidence. Forsch Komplementmed, 20(6), 444-53. doi: 10.1159/000357765.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24434759

Patterson, R. E. & Sears, D. D. (2017). Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu Rev Nutr, 37, 371-393. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064634.

LINK: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064634

St-Onge, M. P., Ard, J., Baskin, M. L., Chiuve, S. E., Johnson, H. M., Kris-Etherton, P. & Varady, K.; American Heart Association Obesity Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Stroke Council. (2017). Meal Timing and Frequency: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation,135(9), e96-e121. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000476.

LINK: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/135/9/e96.long

Stockman, M. C., Thomas, D., Burke, J., & Apovian C. M. (2018). Intermittent Fasting: Is the Wait Worth the Weight? Curr Obes Rep, 7(2), 172-185. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0308-9.

LINK: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs13679-018-0308-9

Teng, N. I., Shahar, S., Manaf, Z. A., Das, S. K., Taha, C. S. & Ngah, W. Z. (2011). Efficacy of fasting calorie restriction on quality of life among aging men. Physiol Behav, 104, 1059–64.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21781980

Teng, N. I., Shahar, S., Rajab, N. F., Manaf, Z. A., Johari, M. H. & Ngah, W. Z. W. (2015). Improvement of metabolic parameters in healthy older adult men following a fasting calorie restriction intervention. Aging Male, 16, 177–83.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24044618

Tinsley, G. M. & La Bounty, P. M. (2015). Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutr Rev, 73(10), 661-74. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv041.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26374764

Varady, K. A., Bhutani, S., Klempel, M. C., Kroeger, C. M., Trepanowski, J. F., Haus, J. M., Hoddy, K. K., & Calvo, Y. (2013). Alternate day fasting for weight loss in normal weight and overweight subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J, 12, 146.

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24215592

Witte, A. V., Fobker, M., Gellner, R., Knecht, S., & Flöel, A. (2009). Caloric restriction improves memory in elderly humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(4), 1255–1260. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0808587106

LINK: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2633586/

Leave a comment for us below, we appreciate your feedback!

Intermittent Fasting and Working Out

The entire contents of this website are based upon the opinions of Build Holistic Nutrition. Please note that Build Nutrition is not a dietitian, physician, pharmacist or other licensed healthcare professional. The information on this website is NOT intended as medical advice, nor is it intended to replace the care of a qualified health care professional. This content is not intended to diagnose or treat any diseases. Always consult with your primary care physician or licensed healthcare provider for all diagnosis and treatment of any diseases or conditions, for medications or medical advice, as well as before changing your health care regimen.

© BUILD NUTRITION 2024. ALL RIGHTS RESERVEd PRIVACY POLICY

Go ahead, creep us on social. You know you want to!